Where have all the good songs gone? A critique on the sad postmodern state of contemporary pop music

Despite some great, hospitable times had working within the music industry, I see the insidiousness of much of it more clearly now, especially all the mental and physical abuse that ran, and still runs, rampant within its ranks. I used to sense it amid whispers along company corridors when I worked full-time in music journalism.

We’re all familiar with the high levels of corruption in the industry so far as record-selling goes, and we’re becoming more and more enlightened over the once-hidden stories of abuse of artists, but covert corruption extends beyond the A&R and financial sides of the music business, now flooding into the creative arena.

Creativity in music, so far as I can hear, has gone the absolute way of commercial and, for the most part, disposable. In fact, most songs that are passing themselves off as real music today teeter on the border of being just plain crass.

Everything is rehashed, the wrong people are being rewarded, and credibility now comes in the form of an electronically-effected (basic) vocal, a throw-it-and-if-it-sticks attitude, and a set of marketable tits (be it those of Sabrina Carpenter, or – ooooof – Sam Smith. The songs? Well, they’re only secondary to the main aim of making money real fast, meaning much more borrowing of yesterday’s audio arsenal, and more slap-dash delivery via inferior electronic means.

Pop music, while still a great release for many, is now almost utterly void of originality. No longer simply sampling or interpolating better bits of the past for the assumed reason that it is running out of ideas (it’s not). Sure, there are many excellent fledgling artists aching to be heard but hardly given the chance – with focus instead on the Insta-moneybringers.

New pop darling, Sabrina Carpenter, not only borrows her aesthetic from pop pin-ups of the past – from Marilyn Monroe to Italian PM Ciccionlina – her music consists primarily of beats, riffs and lyrics from songs of the past. Her biggest hit Espresso uses a splice loop by an artist named Oliver, while her song Please, Please, Please samples Pink Floyd’s infamous hit Another Brick in the Wall. Heck, her song Slim Pickins goes so far as to sample the notification sound from gay hook-up app, Grindr, no doubt picked up quickly by her ardent queer following.

For the most part, pop is on a course to devouring itself through greed, with record companies buying up as much of the music and lyrics as they can, cramming these into AI software, and unleashing the artificial output onto the masses like swathes of anaesthetising, mind-numbing medication – mass audiences more than happy to swallow the mundanity whole.

Modern-day listeners of mass-distributed music don’t even recognise the spell that they’re under. Or maybe they’re just better at this Matrix stuff than I am. But it’s a fair call to say that listening to pop songs today is like hearing an audiobook from the military on ‘How to Kill Your Independent Thinking in Under Two Minutes’. You hear the hum-drum marching over the airwaves of commercial radio, while community stations play all the talent, with a fraction of the exposure and less than that of the takings. Community radio-played artists truly do warrant more of all of our attention but rarely receive it.

Back to sounds from the other side, the big record companies have bought up a heck of a lot of music copyright lately, seemingly with the aim of having near-to-total control of the archives of music so that it can bastardise it to full effect in the name of profit and power (real artists, take heed). It has been sampling from the libraries of audio for years but only recently has it realised: why take a snippet of the great sounds when you can buy the entire digitised cash cow?

Just listen to the songs being played on commercial hits radio today, where a huge majority of them sound familiar simply because the artists and ‘creators’ are ripping off songs of yesteryear – and rarely in a good way.

The original artists are often not even paid because, that’s right, the record companies own a lot of the copyright now. All it takes is a little manipulation with editing suites like Ableton or Audition – et voila! – tons of ‘new’ tunes for the sedated listeners to download by the algo-load. The poaching and pillaging are everywhere. I should know, I like to create sample-laden dance tracks myself as a hobby, never making money from my art but occasionally gifted by The Piper with a solitary Like or a go-ahead sample clearance on YouTube. It’s a beautiful thing when a band like U2 or Sparks or Soulwax grant you permission to use their music to your selected visuals. These are the gods of the gift of music. One day, hopefully, one of their riffs or catchy lyrics will coax us out of senility. But to the brain damage of the here and now, I’m going to list a few modern megahits and their backstory here:

Taylor Swift’s penwomanship is impeccable and songs like Blank Space, Shake It Off and Look What You Made Me Do stand as some of the greatest pop songs made. I had no idea until now that the latter track used Right Said Fred’s novelty song I’m Too Sexy as the basis for its beats and melody. The song’s lyrics page (on Genius and Lyrics.com) now contains the rightly due credits to Fred and Richard Fairbrass, the brothers who wrote I’m Too Sexy, but that was only after legal intervention. Still, other artists who can barely afford a copyright lawyer, least of all a bad-habit limo life like Ed Sheeran’s, aren’t as fortunate in seeing such due credit.

Whoever wrote Swift’s 2025 single ‘The Fate of Ophelia’, it seems they’ve been listening to lots of Lana Del Ray, and the video – while an absolute masterclass in music clip making – has old Hollywood to thank for all its big-production-number ideas.

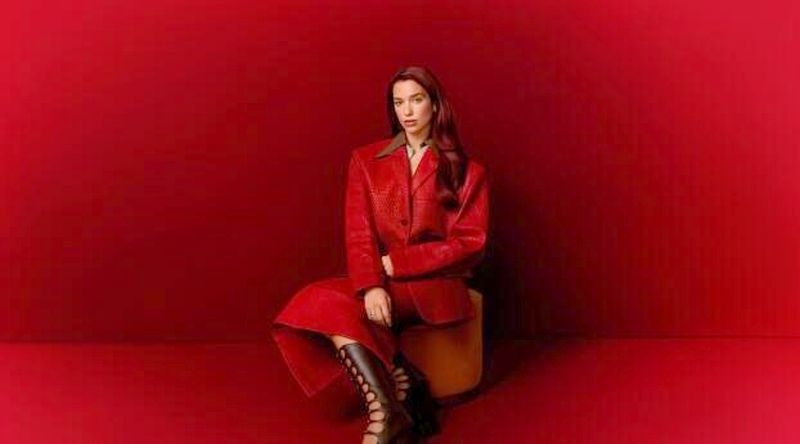

The megahit factory continues: Dua Lipa, whose music I’ve often listened to and loved (Levitation with Madonna is truly next-level artistic genius) has more recently left a few musicians out of work or underpaid. Her song Break My Heart features obvious interpolations of INXS’s Need You Tonight, while her single Prisoner is a lo-fi simulacrum of KISS’s I Was Made for Loving You, with its chorus a diluted version of Olivia Newton-John’s Physical.

Dua Lipa: ‘borrowing’ a heck of a lot of music from the past to ‘create’ her contemporary hits.

The DJs-turned-producers are also selling out, with David Guetta pushing Bebe Rexha up front to sing I’m Good, which heavily samples the 1998 club track Blue, turning an annoying song into something even more maddening. Even Eminem appears to have lost all originality (not that he had much to begin with). His single Houdini is catchy enough, but all the best bits are owed to Steve Miller Band’s Abracadabra. I could go on for pages, but I won’t bore you – the music should be doing a good enough job of that already.

The new dirty word on the pop music scene is ‘interpolation’, which is basically an artist taking a melody from a formerly great song, recording a watered-down version of it, then singing new words over the top of it. It’s a far cheaper option than having to pay and get permission to use the actual source from the original artist.

Eminem is renowned for interpolating or sampling hits of yesteryear and weaving them into his rap tracks.

At university in 1990, I enrolled in an honours degree and was set to write a thesis that would observe the postmodern state of the music scene. I hypothesised that within three decades’ time, a huge portion of the pop charts would consist of cover songs and music sampled from the past as their basis. I never got to complete that thesis due to having a car accident part way through the course. Little did I realise then that my theory would leak into the film and gaming industries, too, with production companies now wishing to sample the voices of actors so that they can hold them forever in their treasure troves of copyright ownership. Again, it means more money for the shady captains of industry and far less for the artists themselves. It also could lead to the ultimate killing off of art, turning it into a fully capitalised venture.

Keanu Reeves loans his voice (for a price, of course) to that of main character Johnny Silverhand in the video game ‘Cyberpunk 2077’. By that actual year, his voice will certainly be owned by game creators and film makers.

I’d like to consider this article a mini finished version of that thesis I began some 30 years ago. I was entering the media force around that time, too, and I’ve seen it survive through all the ups and downs, the explosions of new technologies, the downfall of industry big-wigs, and the survival of many who have been in it for the right reasons.

While referentialism is currently rampant, I believe music will never die. In its truest form it is manna from the heavens, delivered through dedicated conduits and arriving at just the right time when we need it. It might be a cherished song that’s suddenly playing on the radio when you need that perfect slice of ear-candy to cheer you up, or an earworm of a lyric that weaves through your mind, providing a word of caution or advice, instruction, or just a nice smile from its glorious melody.

Great music is also strong enough to rise above all the shoddy reiterations and bastardisations we’re hearing today, hopefully making its way back to the top shelves due diligence sometime in the near future. And if the radio DJs and Spotify curators don’t play the good songs for us, we’ll just have to rummage through record stores again to score the genuine quality product.

This article features in edited form in the new book Conversations with Culture Icons by Cream’s editor, Antonino Tati. The book is available in e-format, paperback and hardcover.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply