We test AI’s translation of the opening lines in popular literature… surprisingly it sets the scenes up quite nicely

A.I. almost did a good digi-job of this pretty stack of books, except what’s that redundant bit of board between the top and second one? It often stuffs up with some very minor but totally unnecessary detail. Funnily enough, it actually did well in positing us into the setting of these popular literary texts. Read on.

I find it difficult to imagine a life without books. Even amid a relentless digital world – one with ongoing media everywhere we turn – if I didn’t have a physical book in my hands on occasion whose pages invite me to dive into, I think I’d go mad.

Seemingly infinite genres of literature at cool new bookstore Boundless Books

In celebration of all things physical lit, the 23rd of April is actually World Book Day. Initially having started out as a charity event held annually in the United Kingdom and Ireland on the first Thursday in March, it somehow bookwormed its way into the month of April is now celebrated pretty much all around the world.

On World Book Day, every child in full-time education in the UK and Ireland is provided with a voucher to be spent on books – now that’s pretty neat. And a great idea that might take off in Australia some day.

Anyway, to celebrate this special day, Cream has turned to classic literature and roped in that modern menace – AI – to see what it has to say about the classics.

Basically, I wondered if AI would be clever enough to set scenes by ‘reading’ the opening lines only from popular novels.

I utilised the app Deep Dream Generator and fed the following books’ opening sentences to see what images would come out of it. To test it, I first keyed in the opening paragraph to HG Wells’ The War of the Worlds which reads (sorry, bit of a long one but skip if you know it):

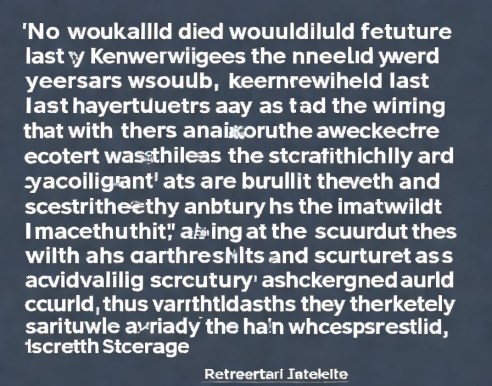

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.

The image generator picked up key nouns, verbs and descriptions, turning them into a ‘collage’ (or ‘montage’) featuring (usually literal) descriptions. It’s when metaphors have been used in writing that the scene starts to get a little trippy.

Since you can opt for a particular style model – ‘photo real’, ‘artistic’, ‘fantasy’ and so on – I thought I’d try two. ‘Artistic’ translated visually to this:

When I swapped the AI model from ‘artistic’ to ‘cyberspace’, things suddenly got a little scary (rather Orwellian, actually). Instead of a landscape picture or composite portrait, I got a regurgitation of gobbledygook that looked unnervingly alien. It’s like the artificial intelligence was trying to send me a message about the sentences I’d just keyed in. Creepy, really.

Anyway, sticking to two styles – here are 13 more famous texts fed through the Deep Dream AI image generator (in ‘photo real’ and ‘artistic’ modes).

Whether artful landscapes or picture-perfect portraits, most of the AI output was pretty much on the mark… but you be the judge.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

3 May. Bistritz. — Left Munich at 8:35 P. M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late.

Critique: It’s pretty spot-on, except we don’t think the original Dracula would have had his streets lit up so brightly.

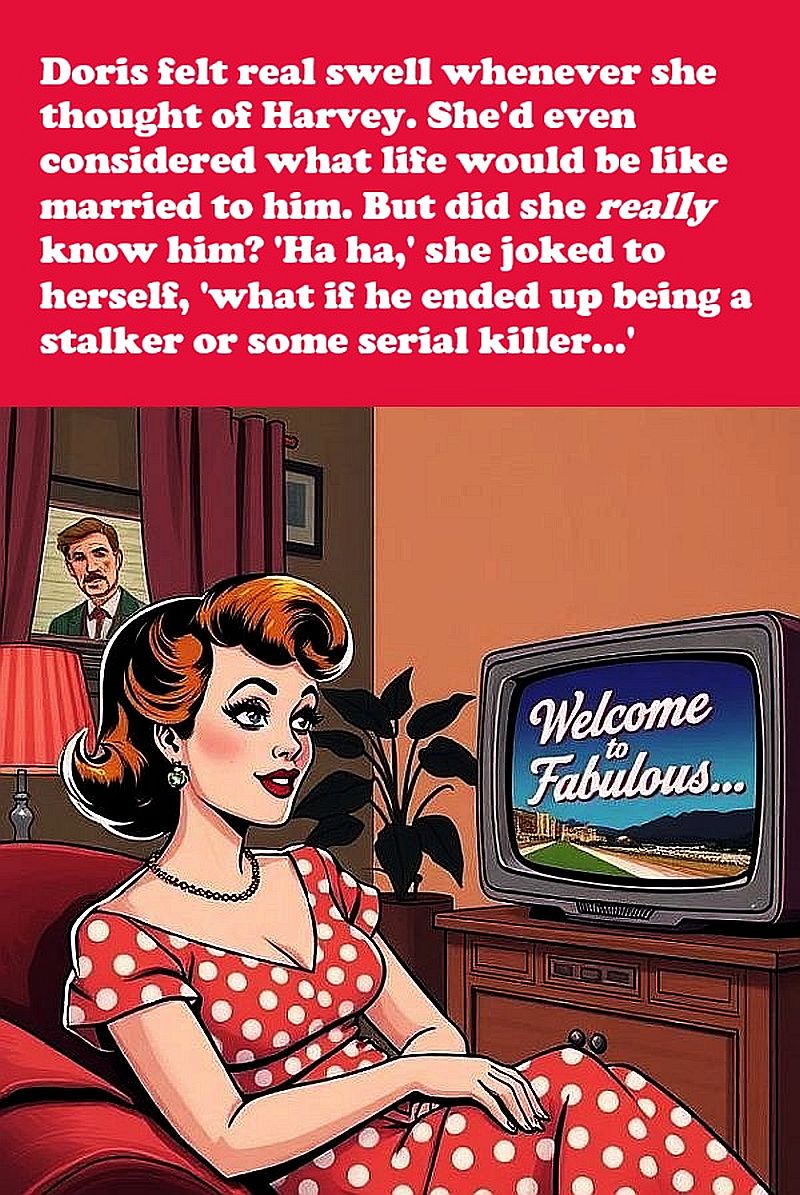

Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives

The Welcome Wagon lady, sixty if she was a day but working at youth and vivacity (ginger hair, red lips, a sunshine-yellow dress), twinkled her eyes and teeth at Joanna and said, “You’re really going to like it here! It’s a nice town with nice people! You couldn’t have made a better choice!”

Critique: Close to what you’d imagine when reading the words on the page. And yes, that is a sunshine-yellow dress beneath her coat.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Chapter 1. I am by birth a Genevese, and my family is one of the most distinguished of that republic. My ancestors had been for many years counsellors and syndics, and my father had filled several public situations with honour and reputation.

Critique: It’s like she’s jumped straight off the page!

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Act I, Scene I. Elsinore. A platform before the castle. Francisco at his post. Enter to him Bernardo. Bernardo: Who’s there? Francisco: Nay, answer me: stand, and unfold yourself. Bernardo: Long live the king! Francisco: Bernardo? Bernardo: He.

Critique: Yasssss, very ye olde Shakespearean.

Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange

There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening. The Korova milkbar sold milk-plus, milk plus vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom, which is what we were drinking.

Critique: This looks like a reject shot from a Strokes’ photo shoot circa 1999.

Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Critique: I see the Light, I see the Darkness, I see the despair. Especially in those cushions.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway

Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer’s men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning – fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

Critique: They’ve done a bang-up job with the Virginia Woolf nose – even better than Nicole Kidman’s prosthetics in ‘The Hours’.

Antoine De Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince

Once when I was six years old I saw a beautiful picture in a book about the primeval forest called True Stories. It showed a boa constrictor swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing.

Critique: Can’t spot the boa constrictor but it’s amazing they got some boab-looking trees in there considering these are not mentioned in the intro.

Dr Seuss’ Green Eggs And Ham

That Sam-I-am, That Sam-I-am, I do not like that Sam-I-am; Do you like Green Eggs and Ham?

Critique: Steady on, bit of a wide gutter…

Which Celebrities Have the Most Fake Followers on Social Media? Katy Perry tops the list

James Joyce’s Ulysses

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.

Critique: Stately, plump Buck Mulligan best be careful shaving that moustache. Seriously, that mouth and mo’ montage is freaky.

Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach

Until he was four years old, James Henry Trotter had a happy life. He lived peacefully with his mother and father in a beautiful house beside the sea. There were always plenty of other children for him to play with, and there was the sandy beach for him to run about on, and the ocean to paddle in.

Critique: Fairly plain and simple, like the prose itself.

Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time: The Eye of the World

There are neither beginnings nor endings to the turning of the Wheel of Time. But it was a beginning. Born below the ever cloud-capped peaks that gave the mountains their name, the wind blew east, out across the Sand Hills, once the shore of a great ocean, before the Breaking of the World.

Critique: Very much how fantasy readers would have expected the setting to look like. All that’s missing is the two rivers, though these aren’t mentioned in the intro.

Walking Through Italy: Immersive Local Experiences Along the Way

Interview with Jeff Lindsay: author of the ‘Dexter’ novels and consultant to the series

Ground Control to Major Don: 60 Years of ‘Lost in Space’, an interview with actor Mark Goddard

↑ Wanting this cute ceramic mug tributing The Beatles.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.